By the middle of the 19th century the Industrial Revolution had exhausted the various styles and themes recognised in the decorative arts. Over-mechanisation and mass production were seen in certain artistic circles as creating pieces that were merely a reflection of what had gone before. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was perceived by some to be the culmination of all that was wrong in design and production at the time. The 17-year-old William Morris saw it as “wonderfully ugly” and believed it represented “all that was bad in an industrial age”, while John Ruskin branded it “morally decadent”.

The Arts & Crafts Movement: exponents, ethos and evolution

Justin Roberts, Jewellery Specialist, Historian and Lecturer, considers this most British of trends which from modest origins was to be interpreted throughout much of the world.

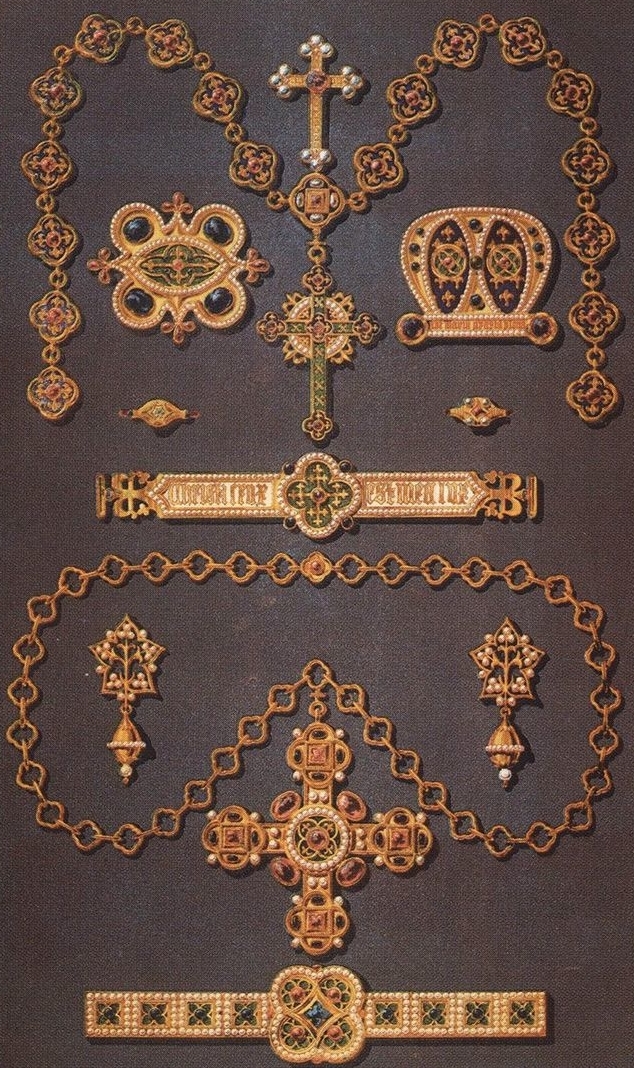

Image 1: All the fittings here, except for the frescoes and sculpture, are the work of the English architect, designer and critic, Augustus Pugin and survive largely unaltered. Remembered for pioneering the revival of the Gothic style in architecture, Pugin's work culminated in designing the interior of the Palace of Westminster

During the 19th century the Gothic revival, under the auspices of Augustus Pugin (see images I and 2) had sowed the seeds for an alternative route: an interest in Medievalism and an appreciation of the lost crafts of the pre-Industrial age, combined with the signs of handiwork, flaws and imperfections were welcomed as indicators of individualism. Artists were quick to adopt the religious and mystical symbolism so common in Medieval art – the galleon as a symbol of the Elizabethan Age of discovery and adventure, or the Peacock, a symbol of immortality and resurrection.

Image 2: Augustus Pugin, jewellery designs, presented at the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry, 1851. Made by Hardman of Birmingham | Drawing from: The Industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century

In addition, the opening up of Japan to the West generated significant interest in the country’s arts, culture and products, notably silks, lacquer, porcelain and metalware. The clean, linear lines seen in Japanese art were to heavily guide the work of designer Christopher Dresser, ironically this style pre-empted the Art Moderne movement of the 1920s (see image 3).

Image 3: Minton ceramics, one of a pair designed by Christopher Dresser, c. 1872-1880.

The shape of these vases copies that of a Japanese bronze, and the source of inspiration for the decorative pattern comes from both China and Japan. These vases reflect one aspect of Dresser's deep interest in Japanese art, which informed his work in regard to both shapes and decorative schemes | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

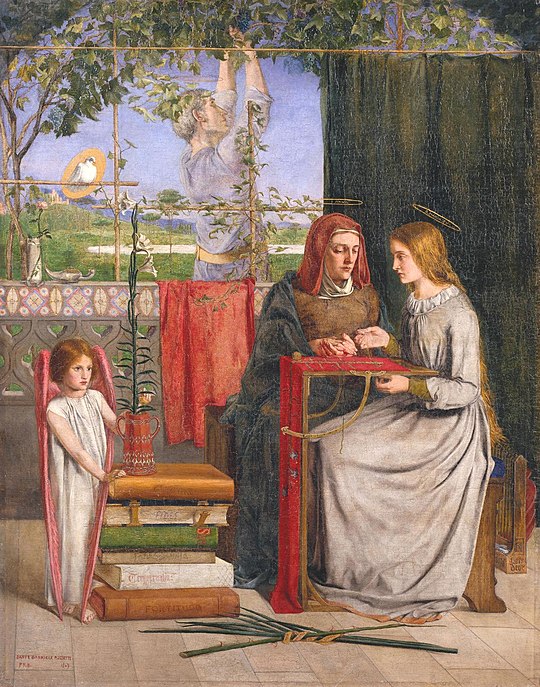

One of the major artistic influences of the period can be traced to the activities of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Founded in 1848 by artists William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, the society’s mantra was to create art suitable for the modern age expressed through a magic and symbolic realism which harked back to the Medieval Age and the art of 15th century Italy (see image 4).

Image 4: The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1848-49, oil on canvas | Tate Britain, London

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a society of young British painters who found inspiration in Italian art of the 14th and 15th centuries. Although the Brotherhood's active life lasted not quite five years, its influence on painting in Britain, and ultimately on the decorative arts and interior design, was profound.

The fusion of these various design movements helped to forge the new English style, which developed in reaction to the extreme systemisation seen in high Victorian design. Mass production characterised mainstream Victorian culture, whereas the new aesthetic championed individuality. English Arts & Crafts’ design ethos was rooted in Britain’s Medieval and Celtic past. There was a strong correlation between jewellery designers and painters: they all moved within the same artistic circles, and many artists who had started their careers as painters or architects saw the creation of jewels as the natural extension of their oeuvre.

Image 5: A silver, gold, garnet, blister pearl and diamond peacock brooch, designed by Charles Robert Ashbee and made by the Guild of Handicraft circa 1900.

Family tradition stated that this brooch was designed by Ashbee for his wife Janet | Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The Guild of Handicraft, established in London in 1888 by the young radical architect Charles Robert Ashbee, became one of the foremost Arts & Crafts’ workshops of the period. Influenced by the ideas of William Morris, Ashbee’s aim was to establish a craft guild based on the Medieval example.

Image 6: A silver, gold, opal and peridot peacock brooch by Charles Robert Ashbee, the neck of the bird decorated with polychrome enamel

In 1901 the Guild relocated to the Cotswolds market town of Chipping Campden in order to create a colony along the lines of the Darmstadt Colony of Jugendstil artists in Germany. The focus was on communal life: some 150 artists and craftsmen lived and worked away from the industrial metropolis of London, enabling Ashbee to create a new society based on the socialist ideals and principles of the Medieval guild. The Guild specialised in metalworking, producing jewellery and enamels as well as hand-wrought copper and wrought ironwork. Ashbee himself designed jewels, frequently based on the popular Guild motif of the peacock. In the early 1900s he designed 12 brooches and a necklace based on this subject, the most iconic being the brooch he created in 1900 for his wife Janet, (see images 5, 6 and 7).

Image 7: A gold, gilded silver, turquoise and enamel brooch designed by Charles Robert Ashbee and made by the Guild of Handicraft circa 1903. Together with the peacock, the ship was a favourite motif of Ashbee's, but it was also popular amongst other Arts & Crafts designers in Britain, America and Scandinavia | Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Although initially successful, the inevitable economic realities of the model made it impossible for the Guild to compete with the machine-made and less expensive items produced in volume in Birmingham by its competitors. As the movement’s exposure and popularity grew, it became clear that the consumer admired the aesthetics of the Medieval past but didn’t want to pay high artisan rates for it. The reality was that the Guild would never be commercially viable unless it watered down its desire to pursue a socialist utopian dream, and so it closed in 1908.

Image 8: A Cymric gold and enamel pendant designed by Archibald Knox for Liberty and Co. | Victoria & Albert Museum, London

However, the continued enthusiasm for the new movement based on a Medieval and Celtic heritage was embraced by the firm of Liberty & Co.

Image 9: A gold and peacock blue enamel necklace designed by Archibald Knox for Liberty & Co.

Founded in 1875 by Arthur Lazenby Liberty, a Regent Street draper, Liberty popularised these designs and made them readily available to the public by, paradoxically, adopting the mechanisation abhorred by the early founders and cleverly employing some of the renowned Arts & Crafts designers, such as Archibald Knox, Jessie King and the husband-and-wife partnership, the Gaskins, (see images 8, 9, 10 and 11).

Image 10: A silver and enamel buckle, probably designed by Jessie Marion King and produced around 1903 by Hasler & Co. for the Liberty & Co. Cymric range.

King was a designer based in Glasgow and this jewel shows the influence of the distinctive Glasgow style best known through the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh | Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Such was his success that ‘Stile Liberty” was adopted in Italy to define the local variant of Art Nouveau. Liberty’s clients included members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and such luminaries of the age as Oscar Wilde who remarked that “Liberty is the chosen resort of the artistic shopper”.

Image 11: A silver, opal and glass pendant, circa 1920, designed by Georgie Gaskin. The design, characterised by closely-packed leaves and flowers sprinkled with gemstones is typical of the work of Georgie and Arthur Gaskin | Victoria & Albert Museum

On stage, Miss Lily Brayton, the Victorian Shakespearean actress, accessorised her Medieval costume with one of Archibald Knox’s Liberty necklaces, (see image 12).

Image 12: Lily Brayton, (1876-1953), portrait | National Portrait Gallery, London

Through his Celtic-inspired precious metal and pewter wares Archibald Knox became a household name, he titled the gold and silver range ‘Cymric’ and the pewter ‘Tudric’ to evoke the golden age of the Tudors. In jewellery, silver was employed as much as gold, while cabochon stones, and blister pearls were favoured for their irregularity, and hammered decoration and rivets were appreciated as evidence of the maker’s work. Liberty produced platinum jewels too, set with black opals, aquamarines and diamonds, configured into iconic Celtic ornaments, as far removed from the mainstream Belle Époque jewels of the Garland Style as can be imagined, (see image 13).

Image 13: A gold, opal and seed pearl necklace, by Liberty & Co., the use of Australian black opals became popular with Arts & Crafts jewellers. Note also the Celtic influence in the overall design

There was a strong correlation between the new English Arts & Crafts style and similar crafts movements in continental Europe, such as the Jugendstil style of Germany. The Anglo German firm Mürrle, Bennett & Co., founded by Ernst Mürrle and John Bennett is a good example of this phenomenon: with strong stylistic similarities to the designs of Archibald Knox, their jewels became widely fashionable and were sold through Liberty & Co. (see image 14). Arts & Crafts’ influences also spread through Scandinavia and the Russian empire, drawing inspiration there from the pan-Slavic style of Medieval Russia.

Image 14: A gold, turquoise, freshwater pearl necklace by Mürrle Bennett. The wholesale business of Mürrle Bennett (Ernst Mürrle and J.B. Bennett) opened in London as Siegele & Bennett in 1884 advertising in 1891 as 'manufacturers and importers of British and Foreign jewellery also at 39 Bleich-strasse, Pforzheim'. The firm was renamed Mürrle, Bennett & Co.

From humble beginnings forged as a reaction against the saturated designs of the Victorian age, Arts & Crafts was to operate on a global scale and unlike its Art Nouveau cousin continued to flourish and evolve after the First World War.