During the Summer of 1901, while all of London was mourning the death of Queen Victoria, Pierre Cartier was called to Buckingham Palace at the request of Queen Alexandra to commission a necklace of Indian design to complement three Indian gowns she had received from Mary Curzon, wife of the Viceroy. The necklace was to be created incorporating some of the many Indian jewels that the Royal family had accumulated over the years which had been originally designed for men and were unsuited to the fashions of 1900. This commission was to herald the start of a long and prosperous period of Royal patronage as well as introducing Cartier to the exoticism of the Orient.

Cartier's role in the expression of the Indian influence

In his latest article, Justin Roberts, Jewellery Specialist, Historian and Lecturer, explores how Cartier's empathy with the culture, art and aesthetics of India manifested itself in the remarkable jewels created by the firm in the early 20th century.

Image 1: The set of Scheherazade, depicted in a sketch by Leon Bakst, as performed in Paris, 1910, by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.

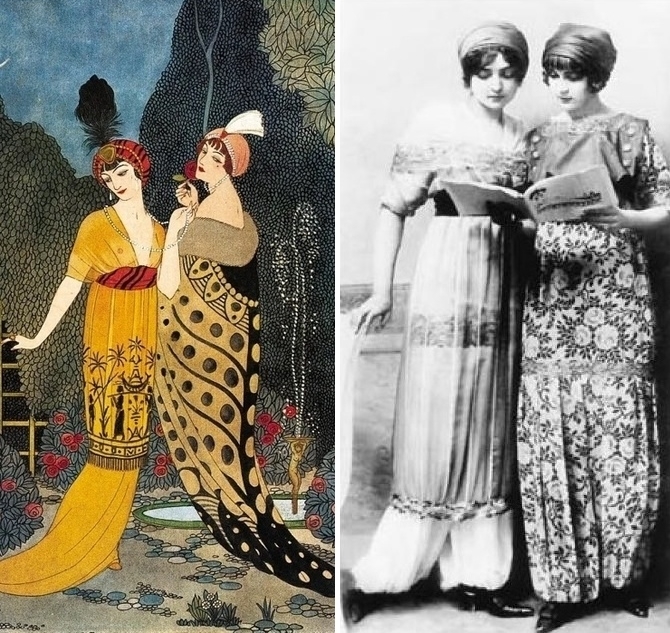

India had always held a fascination for the West, and in part it was thanks to the British Raj that the appeal was strongest in Britain. Providing exotic backdrops to European society the influence filtered through to the Ballets Russes’ Sheherazde (see image 1) and Paul Poiret’s latest Orientalist-inspired fashions (see images 2 and 3). Cartier made no distinction between the various oriental influences, describing his jewels as Indien or Hindou, and he looked to both the Middle East and the Far East, utilising a panorama of ornamental motifs from the Ottoman Empire, Persia, and India. One of the main sources for these decorations however was Louis Cartier’s own collection of Persian miniatures – they enthralled him with their jewel-like quality and provided him with designs for cigarette and vanity case and even exhibition invitation cards.

Image 2: Paul Poiret, evening gowns, 1912 | Image 3: Paul Poiret, sultana skirt and harem pants, 1911

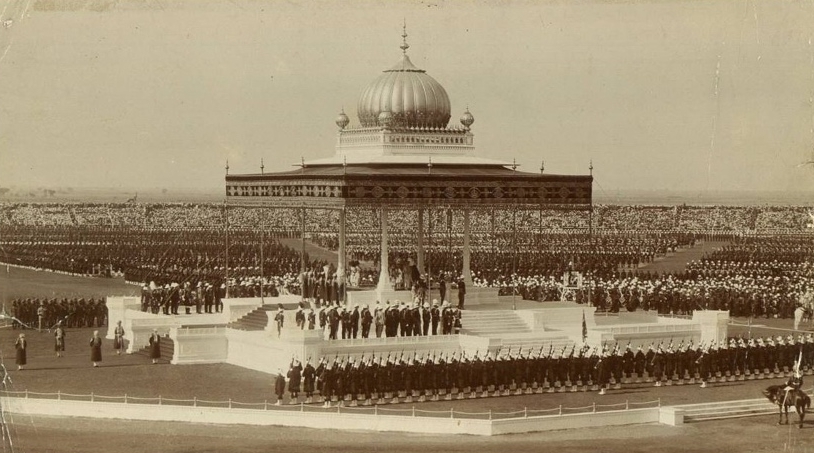

In 1909 the Indian business was handed to Jacques to be run from the London branch, affording him the opportunity presented by the British Raj. In 1911 he was at the famous Delhi Durbar attended by King George V and Mary of Teck, as well as every Indian princely house and nobleman in order to pay homage to the new Emperor and Empress of India, and thereby cementing support for the British Crown, (see image 4). This occasion to field business was not lost on the house of Cartier, and Jacques used the Durbar as an opportunity to identify new clients for the firm from amongst the Indian princes. He also sourced gems and antiquities to be sold from the London branch to European clients.

Image 4: The Delhi Durbar, 1911.

On his return to London in 1912 the London branch of Cartier held an exhibition of Oriental jewels, showcasing jewels both inspired by Persian Art and others incorporating antique elements, as well as exhibiting both antique and modern Indian jewels unaltered. Later on in the 1920s and 30s Cartier began to incorporate older elements into newly fashioned designs (see image 5).

Image 5: Pearl, emerald and diamond pin, Cartier, circa 1925, in the shape of a sarpech, the turban ornament worn by significant Hindu, Sikh and Muslim princes in India, but also by notable men in Persia and Turkey.

One of the characteristics of Indian jewels that fascinated Cartier was the use of carved gems – emeralds and rubies formed various floral motifs and in some instances birds and animals. Previously such stones were perceived as primitive and of little value, and they did not appeal to Western European taste, however Cartier diamonds and onyx. The style soon became one of Cartier’s signatures and today is known the world over as ‘Tutti Frutti’ (see images 6 and 7). The use of colour with these new found exotic gems from the East appealed to the sensibilities of the new Art Deco look and it was not long until other jewellers began to follow, although none have eclipsed Cartier in this genre. Henri Picq was the principal workshop working in this style and was soon supplying Cartier with an array of jewels in the new style of the Indian aesthetic.

Image 6: 'Tutti Frutti' bracelet, Cartier Paris, circa 1930

Image 7: 'Tutti Frutti' clips, Cartier, circa 1930

One of the most iconic ‘Tutti Frutti’ jewels was the necklace created for the socialite Daisy Fellowes in 1936. It was fashioned from three existing Cartier jewels in her collection purchased in the 1920s; the necklace was created with a corded back chain emulating traditional Indian jewels but incorporating carved sapphires to complement the Indian rubies and emeralds, a colour combination which not been seen before in traditional Indian jewellery (see image 8).

Image 8: Cartier's famous 'Collier Hindou' designed for socialite Daisy Fellowes in 1936 and altered in 1963, and a pair of carved emerald and diamond pendent earrings by Cartier, 1936.

Another equally memorable jewel was the emerald and sapphire sautoir illustrated in Vogue in 1927. It was set with three carved Mughal stones to a sapphire bead chain of pale Kashmir sapphires. This marvellous jewel was purchased by Baron de Rothschild for his new wife, the celebrated divorcee Catherine Wolff, or “Pretty Kitty” as she was better known. Another heiress, Majorie Merriweather Post, also embraced the new Hindou style. Her wonderful Art Deco shoulder brooch created in 1928 and set with Mughal emeralds can be seen today at the Hillwood Museum, her former estate, in Washington DC, (see image 9). The brooch was the prominent, central focus in the 1929 portrait of Mrs Hutton (Majorie Post) and her daughter painted by the Italian artist Giulio de Blass (see image 10).

Image 9: Marjorie Merriweather Post's imposing emerald and diamond brooch created by Cartier in 1923 and altered in 1928 | Image 10: Marjorie Merriweather Post, Mrs Edward Hutton (1887-1973), wearing the emerald and diamond Cartier brooch, with her daughter, Nedenia Hutton (1923-2017), portrayed by Giulio de Blaas in 1929.

As well as the Indian inspired jewels created to appeal to Western taste, Cartier also re-modelled historic jewels for the Indian princes. Interestingly, they preferred the use of platinum over the traditional Indian preference for gold and were swayed by the fashion for Art Deco that was taking hold. The culmination of such commissions was an exhibition held by Cartier in Paris in 1928 featuring jewels re-mounted for the Maharajah of Patiala (see image 11).

Image 11: The 9th and last Maharaja of Patiala, (reigned: 1938-1947), Sir Yadavindra Singh (1913-1974), wearing jewels remounted by Cartier for his father, Sir Buphindra Singh.

Cartier has continued to hold sway over the interpretation of Indian inspired jewels, even today embracing the exoticism of the East with new versions of its iconic ‘Tutti Frutti’ jewels. However, despite these contemporary examples, the jewels of the 1920s and 30s still retain their power to capture the imagination through their extravagant expression of the Orient.